Why comics belong in schools…and more ideas from graphic novelist Gene Luen Yang

Gene Luen Yang taught high school science for 17 years while moonlighting as a graphic novelist. Today, both art and education get celebrated in his work. Ten years after his book American Born Chinese became the first graphic novel to be nominated for a National Book Award, the Library of Congress appointed Yang the National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature — which, he says, “was one of the best days of my life.”

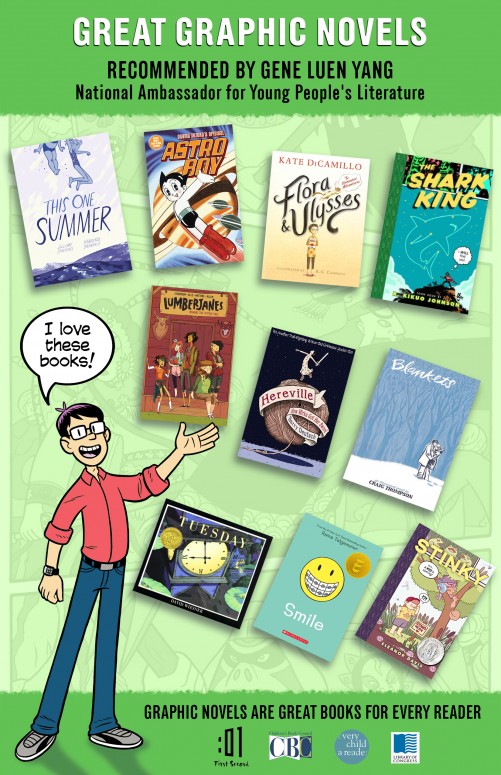

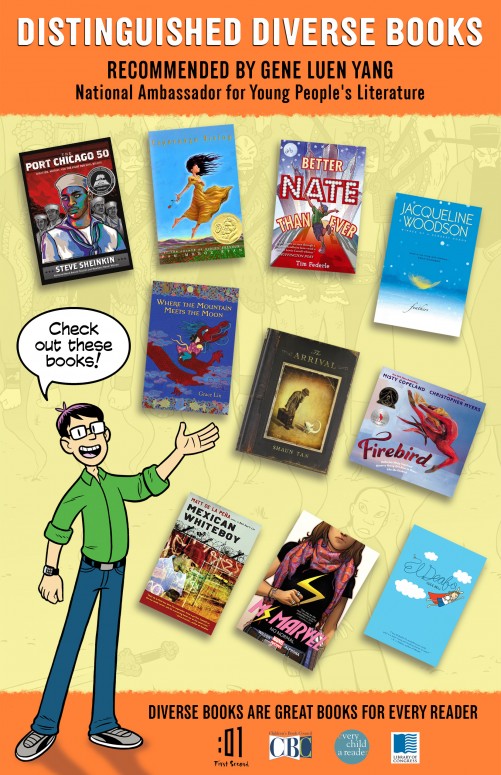

Yang recently spoke with TED-Ed before heading to Comic-Con International in San Diego. Below, check out his recommended reading lists for kids, his thoughts on writing the Chinese Superman, and his advice for teachers on how to use graphic novels in schools.

What were you like as a kid?

I was pretty much a textbook nerd. I liked all the things that nerds are supposed to like. I liked computers; I started coding when I was in sixth grade. I liked comic books; I started collecting comics when I was in fifth grade. I liked to draw; I was always drawing in class. I liked comics, I didn’t like sports. But there were definitely kids who liked both, and I think that artificial divide between athletic activity and nerdy activity is breaking down. I was not an awesome student. I don’t think I was terrible, but I also wasn’t great. There are certain subjects that I really liked, and I would pay attention during those subjects, and then the other subjects I’d have a hard time with.

When did you realize that you wanted to be a graphic novelist?

When I was really little, I wanted to be in animation — I wanted to be a Disney animator; that was my lifelong goal. And then after I started collecting comics in fifth grade, I slowly switched over. I think it solidified for me when I was in college and I took a summer-long animation class, and during that summer, I produced like two, three minutes of animation total. That’s when I realized that animation is so labor-intensive that it’s actually very difficult for one person to have control over an entire project. I mean, comics is really labor-intensive as well, but at least it’s manageable enough that one person can do it. If you really want to, you can do the whole thing all on your own. So I switched over to wanting to do comics when I was in college. I started self-publishing comics, and then I got involved in a local community of cartoonists who’d hang out all the time, and we’d go to things together.

In the late ’90s comics in America were just doing — the industry was not doing well. The conventions had very low attendance. Nowadays Comic-Con is crazy — it sold out in April. But back then, you could walk up day-of to buy tickets to go in, and then on Sundays, which was the last day of the convention, I remember it seemed like there were more exhibitors than there were attendees, it was just really low attendance, nobody was really interested in comics. People were predicting that the comic book industry was about to die. I don’t know if you remember this, but Marvel Comics had to declare bankruptcy, and people were — some people — were expecting it to just go out of business completely, and if that happened, they were saying it would take out probably the comic shop system within America, because so many comic shops were reliant on Marvel Comics. It was very apocalyptic, and that’s when I was entering comics. People were saying, “You know that comics is going to become this very niche thing in America?” I wasn’t expecting to be able to make any money out of it. I remember going with my friends to comic book conventions and feel kind of depressed afterwards, but we decided that we’d keep doing comics, just because we liked it. We wanted to do it, because we liked it.

So I got a job as a teacher, and I was expecting back then that I would always have a full-time job, and I would just make comics on the side. Some people play golf to relax, I would make comics to relax.

What advice do you have for teachers who want to use graphic novels in a classroom?

There are lots of different ways that comic books and graphic novels can be incorporated into a classroom. The easiest way is to use them with reluctant readers. Comic books and graphic novels are really a gateway into just the habit of reading, and I know a lot of teachers have had success using comics with reluctant readers — just getting them into the habit of reading. I do think comics are worthy of study in and of themselves, though, as well.

Comics are also a great way of getting kids to think critically about the visual media that surrounds them. So unlike a lot of these other visual media out there — unlike film, and television, and animation — in comics, the images are static, so you can — in a comic book, past, present and future all sit side-by-side on a single page, and because of that, you can dwell on a moment as long as you want. And you can do that as a class, or you can do that as an individual reader. And I think it allows you, if you want, to think and read a little bit more critically than is maybe possible with film or animation or television. If a teacher knows what she’s doing, I think she can use comics to teach visual literacy, to teach kids to be critical about the images that surround them. I think we have a tendency to always believe what we see; as a species I think that’s true. We have a tendency to just believe what we see. And I think in today’s world of sophisticated imagery, that doesn’t always serve the student to do that. So comics can be a way of breaking that, of making kids think, not just about the words that they hear but also the images that they see.

As the National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature, I created Reading Without Walls to encourage kids to explore the world through books. I want them to read diversity, and I want them to read diversity in three very specific ways. Number one is I want them to read books about characters that look or live like them. And I especially want them to pick books with covers that feature characters of color. I think there’s this really weird discussion within publishing right now about — I’ve had more than one author of color tell me that their publisher encouraged them not to put a character of color on their books, because they felt like it damage sales. So I want kids to pick books with characters that are of color on the covers.

Second, is I want them to pick books about topics that they might find intimidating. And then third is, I want them to pick books that are in formats that they don’t normally read for fun. So if they normally only read chapter books, I want them to try graphic novels. If they normally only read graphic novels, I like them to give a chapter book or a book of verse a try.

Do you have an idea where graphic novels are going next?

It seems like pop culture is getting more and more nerdy, so the things that used to be really niche — when I was a kid, if you were a superhero fan, if you read superhero comics, you would just kind of hide it. There was no way you would advertise that. In my junior high, there’s no way I would advertise that. And now, even the super popular kids are wearing Spiderman t-shirts and stuff. It seems like we’re still on an upward swing with that kind of stuff. So in the broader pop cultural landscape, it seems like people are becoming more and more aware of superhero comics, at least. And also the fact that every librarian knows what a graphic novel is now. I don’t think you could say that in the mid-’90s.

It also seems like comics are becoming more diverse in America — so for a really long time, comics in America were dominated by superheroes, and now there are just so many options out there. Memoir has become a real force in comics — Raina Telgemeier’s stuff, I think she’s probably the best-selling American cartoonist right now, which again, in the ’90s, I just don’t think she would’ve been able to predict. That trend towards diversity in every sense of the word, I think that is just going to continue as well.

What can you tell us about the latest Superman installment?

The diversity conversation is happening everywhere, and it’s in superhero comics right now. Superheroes are just so American. They’re created in America, they became popular in America. Now people all over the world are — you can find superhero fans anywhere in the world. But they still embody this very American ethos, and I think the diversity conversation as applied to superheroes is really about who can be American. And I think the reason there’s this push for seeing heroes of every identity, period — is really, we kind of want to see a visual representation that anybody can be an American.

The Chinese Superman, in particular — that wasn’t my idea, that was actually the idea of Jim Lee, who’s one of the co-publishers at DC comics — he’s kind of like my boss now; it’s kind of crazy because when I was a teenager, I was reading his comics. He was a fan-favorite artist, and he was working for Marvel back then, and now he’s the big cheese at DC, and he wanted to see an Asian superhero. So the Chinese Superman is not American; he’s a Chinese citizen, he’s not a Chinese-American. But what we want is to take the things in this deeply American genre and see how many of these values translate into another culture — see how much of this stuff is universal, and see how it translates into another culture.

Let’s talk about the future of education and storytelling. What do you think we can expect from the future, as you see it?

First, I think that diversity — in every sense of the word — is going to be a big thing, and different people of different identities and different cultural backgrounds are going to get more and more of a voice — not just on the American stage, but on the global stage. Second, stories are also getting more diverse. I think what’s happening in comics, with the genre diversity within comics, is happening within storytelling in general. We’ll see more and more stories that defy genres, we’re seeing genres break up into multiple sub-genres, and that’s just going to continue to happen.

Within education, I think education is going to become more customized, so it’ll become more individualized. Teachers will have the technologies to serve their students better as individuals, or as an entire class. And I think all that is really awesome. And as the writer of Chinese Superman, I do think that a lot of what we’re going to see within the next two decades, at least, is going to be defined by that relationship between America and China. It’s going to be interesting to see how that develops.

What advice would you give to students, especially those looking for creative ways to turn their life experiences into artistic mediums, as you have done with your graphic novels?

In a lot of ways, I feel very jealous of students today, because I think there are a lot of tools available to them that just weren’t available to me and my generation. If I were just starting today, what I would do is I would make my comic and I would put it out as a web comic series, and I think that there are a lot of kids that are actually doing that right now, and a lot of high school kids are creating webcomics and putting it out there for the world to see. There are a lot of professional comic book artists now that started off in webcomics. Webcomics, when I was starting out, were not really anything — it didn’t come around until a few years later. But I think the internet in general is just such an effective way for a creator to connect with an audience, and if I were starting off, I would take advantage of that.

In addition, when you’re just starting off, it’s really important to get in the habit of creation. The habit is almost more important than the work itself. I tell students who are interested in making anything creative to set up a time regularly to work on their creative work, and to make sure — to think of that time as sacred, to keep it sacred. And then I will say, just never to let perfection get in the way. If you are too obsessed with making things perfect, you’ll never finish — and the feeling of finishing something is so important to have, it has to feel very familiar — finishing a project, seeing a project all the way through. Finishing is more important than perfection.

Love superheroes? Watch the Superhero Science TED-Ed Lesson series here >>

All very interesting. However, Ms. Raina Telgemeier is repeatedly referred to as ‘he.”

Argh. Thank you, this is fixed!

Excellent! Comics Belong in School, University & Daily Life! …..