“Write your story, and don’t be afraid to write it” — a sci-fi writer talks about finding her voice and being a superhero

Nigerian-American Nnedi Okorafor writes the kind of drop-everything, Africa-based fantasy and sci-fi that she never saw on bookshelves growing up. Here, she talks about the authors that shaped her, her inspirations (traffic! jellyfish!) and her collaboration with Marvel.

Nnedi Okorafor is obsessed with bugs. More specifically grasshoppers, but also cicadas, especially in late summer, when they fill up the dusk with song. “I can remember times when I was five or six years old, where I’d catch a grasshopper and just stare, and let it stare back at me for an hour,” she says. “Even now, the idea that all these tiny, hidden worlds are just dwelling — it’s fascinating, plus it’s beautiful and amazing.”

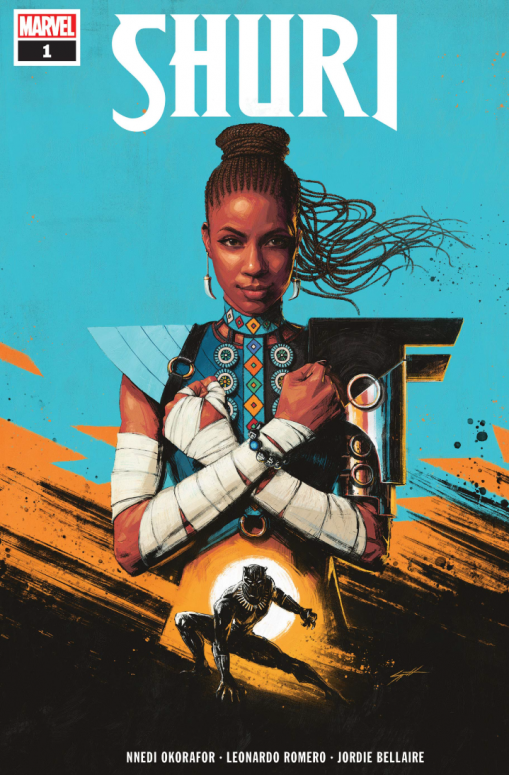

It’s this sensitivity to the wonders around her that has helped make Okorafor one of the most acclaimed writers of science fiction and fantasy today. Over the last decade, in more than a dozen books for children, young adults and adults — including the Binti trilogy, Who Fears Death, the Akata series, Lagoon and, more recently, Black Panther comics, including a brand-new standalone on his little sister Shuri — Okorafor has welcomed readers into her own magical hidden worlds. She has received many major awards, including the Hugo, the Nebula and the World Fantasy Award, as well as the Wole Soyinka Prize for Literature in Africa.

Nnedi Okorafor brings life to Shuri, Black Panther’s little sister, in this new comic book. Image courtesy of Marvel; artwork by Sam Spratt.

Nnedi Okorafor brings life to Shuri, Black Panther’s little sister, in this new comic book. Image courtesy of Marvel; artwork by Sam Spratt.

But you won’t find extraterrestrial colonies, space-trotting imperialist explorers or invading aliens in Okorafor’s work; she avoids these sci-fi tropes. Instead, her settings tend to be African — speculative versions of Nigeria, Sudan and Namibia — and draw on African mythology, folklore and tradition. Her protagonists are typically young women who are caught between cultures and worlds, navigating remarkable circumstances. They include math prodigy Binti, the first of the Himba people to attend a prestigious intergalactic university; Nigerian-American Sunny, a young albino girl with latent magic abilities; and Onye, a half-breed child born from great violence who is on an epic quest to save her people from extinction.

Okorafor’s own experiences of feeling like an outsider have inspired her fictional creations. She was raised in the Chicago suburb of South Holland, Illinois (it was “very racist, very white,” she says), to Nigerian parents who settled in the US due to the Nigerian civil war. “Growing up, in just about every group that I moved in, I was an outsider,” Okorafor recalls. In South Holland, Okorafor was seen as “too black” to hang out with her white neighbors, but on visits to Nigeria, she was viewed by cousins there as being “too American.” As she says, “This idea of being an outsider was something that I was forced to face at an early age, but there was never a time where I felt like I had to try to be someone else to fit in.”

From an early age, she was an enthusiastic reader — but not of sci-fi. She didn’t connect to classic Western works of the genre by authors like H.G. Wells, Jules Verne and Isaac Asimov. “Those books were very white and male, and they presented worlds where the possibility of someone like me wasn’t even there,” she remembers. “I didn’t have to see myself, but it was important to feel it was possible, at least in one of those books, and it was not.” She read a lot of horror fiction, including Stephen King, Robert McCammon, Clive Barker and Mary Shelley. “They presented a world of not just terror, but great imagination,” Okorafor says. “And those stories were a bit more diverse than the science-fiction stories.”

During family visits to Nigeria in the 1990s and 2000s, Okorafor was fascinated by the harmony between traditional belief systems and brand-new electronic devices. “I started noticing the use and the interplay of technology in Nigerian communities, especially when cell phones came around,” she says. “I saw phones popping up in the most remote places, and they were normalized in really cool ways.” She wondered why stories didn’t depict technology in African nations. In fact, she began to wonder why she wasn’t writing such stories herself.

In college, however, Okorafor found herself discouraged from writing science fiction. “I had professors who were constantly telling me, ‘You’re such a good writer; you want to stay away from all of that weird stuff,’” she remembers. “Eventually I just kind of jumped the rails, because I couldn’t help it.” Okorafor dove headfirst into creating the stories she never found on library shelves growing up — ones with strong female protagonists of color, African locations, speculative technology, aliens and magic, as well as complex and relevant social themes like racial identity and gender violence.

“A lot of people are told to stifle their imaginations, just in order to get by. Science fiction does the exact opposite.”

When writing a novel, Okorafor rarely starts at the beginning. And she’s not a fan of outlines. “They feel confining to me,” she says. She begins projects with a strong sense of character and an explosive scene in which that person jumps to life. “Usually, the scene is so strong that I don’t need to know the context,” she says. After writing it, she thinks, “Is there anything else that I want to write with this character?” But how does she go from building a scene to building an entire world? “I do it by being in the world. My character is in that world, and I’m looking through their eyes. All I have to do is look around.”

Okorafor doesn’t revise until she’s at least halfway finished with a story, although often she won’t do so until a first draft is completed. Yet it’s in her self-editing process that the rich political and social themes of her work can emerge. “I’m already a very political person, and I’m very aware of issues,” she says. “So when I’m writing a story, I don’t have to think about it — it comes. In the editing process, I’ll be, like, ‘Okay, oh, I was doing this, let me tweak that a bit, let me strengthen that a bit. Let me weaponize that a bit.’”

Okorafor’s greatest source of inspiration is something we all have access to: the whole wide world. She delights in taking the stuff of everyday life and recasting it in fantastical ways. In Okorafor’s mind, jellyfish evolve into an alien species; traditional Nigerian masquerades become spirits from another realm; and the dense, dangerous traffic of the city of Lagos transforms into a literal road monster that swallows drivers whole. “I definitely have a tendency to notice and revel in those things that most would take for granted,” she says. While she occasionally jots her observations in notebooks, on scraps of paper, and on her phone, they mostly live in her head. She knows they will emerge — somehow, someday. On a trip to Arizona to see the Grand Canyon, Okorafor and her daughter, Anya, were caught in a dust storm. “It was awesome,” she says. “Those things are going to show up in my stories. They just are.”

When she’s feeling stuck — and yes, she gets stuck — she may turn to her daughter for inspiration. “She loves to listen to me tell the story before I even write it,” she says. “In telling the story and having someone who’s listening, asking questions and giving feedback, I find my way. There have been so many times when I’ve gotten ideas or figured something out because I’m doing that with her.” In her 2015 novel Binti, the first person thanked by Okorafor in the acknowledgements is Anya. “When you get stuck, ask a plucky imaginative eleven-year-old what happens next in the story,” she wrote; “you’ll be unstuck in no time.”

“I definitely have a tendency to notice and revel in those things that most would take for granted.”

Now, Okorafor has dove into a completely new genre to her: comics. “I read comics as a kid in the newspaper and in graphic novels,” she says. “I never felt welcome in comic-book shops, so my exposure to superheroes was through Saturday morning cartoons.” But when editors at Marvel approached her last year to write comics in the Black Panther universe, she said yes. She has written four Black Panther issues for Marvel, as well as a three-part series “Wakanda Forever” that follows the Dora Milaje, the all-female special forces team that protects Wakanda. She’s about to release a standalone comic about Shuri, Black Panther’s little sister (a breakout character from Ryan Coogler’s Black Panther film).

In her comic-book writing, Okorafor has been able to flex new creative muscles. “The format has been really nurturing for me, because it’s so different from the way that I create,” she says. Unlike her fiction, she knows from the outset who her central characters are. “It’s easier in that the character’s already alive, but it’s harder in those moments when something about the character previously doesn’t make sense to me,” she says. “Then I have to write around it and deal with it.” Another difference of working in the comic universe: she often starts a project knowing exactly how many pages and how many issues she has to tell her story, as Marvel usually sets those parameters in advance (except for Shuri, which is an ongoing series).

How does Okorafor start writing a comic book? She first writes a short summary of the story that will be told in an issue. Next, she constructs a meticulous outline for the story, beat by beat, with frequent feedback from her editors. Once Okorafor and her team have settled on an outline, she writes the first draft of the script — by hand. “The first draft has to be by hand, because it has to be visual,” she says. “I have a notebook where I draw each panel the way it’s going to be set for the page, and then I write within the panel — and sometimes sketch — what’s happening.” After more rounds of revising and feedback with her editors, the approved draft goes to the illustrators. “It’s a completely different, fascinating process for someone like me, who’s used to writing novels, where it’s very solitary – it’s all you,” she says. “It’s a very collaborative effort, but also you have to think in a different way, which was really tough for me.”

Okorafor doesn’t yet know if she will continue to collaborate with Marvel. “I like to focus on what’s right in front of me,” she says. She is writing a new original comic for Berger Books, set in the same universe as the Binti trilogy and Lagoon, about a community of African and shape-shifting alien immigrants in New York City. The four-part LaGuardia series, illustrated by Tana Ford, will be published in December. Her work may also be coming soon to the small screen — her novel Who Fears Death has been optioned by HBO to be turned into a series, with George R.R. Martin as an executive producer.

“Don’t go changing your story to fit the default — that’s the worst thing you can do.”

In the decade that Okorafor has been writing, she has witnessed a positive shift in sci-fi. She sees greater diversity in who the protagonists are, where stories are set and, perhaps most important, who gets to tell them. But she believes much more work is needed to “de-center” the genre and showcase more stories. “I still think that there is a lack of familiarity with other kinds of voices,” she says. Science fiction has the ability to inspire people who otherwise might feel censored or suppressed. “In various societies — not just American society, but worldwide — a lot of people are told to stifle their imaginations, just in order to get by,” Okorafor says. “Science fiction does the exact opposite. People who are missing that expression in their lives are fulfilled when they read a science-fiction narrative.”

Okorafor’s advice to writers of all ages: Just do it, and do it your way. “Write your story, and don’t be afraid to write it. Don’t go changing your story to fit the default — that’s the worst thing you can do,” she says. “You may be able to find great success, and it works — I’ve seen it work many times — but if you really want a deep shift, and also deep creative satisfaction, you stay true to your own story.”

Watch Nnedi Okorafor’s TEDGlobal talk here:

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Patrick D’Arcy is the Editorial Manager of the TED Fellows program. This piece was adapted for TED-Ed from this Ideas article.