Vegetarian, vegan, flexitarian, pescetarian: Which diet is best for the planet?

The food we consume has a massive impact on our planet.

Agriculture takes up half the habitable land on Earth, destroys forests and other ecosystems, and produces a quarter of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions. Meat and dairy specifically account for around 14.5 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions.

So changing what we eat can help reduce carbon emissions and promote sustainable farming. But there are several “climate-friendly” diets to choose from. The best known are the completely plant-based vegan diet, the vegetarian diet (which also allows eggs and dairy) and the pescetarian diet (which also allows seafood).

There are also “flexitarian” diets, where three-fourths of meat and dairy is replaced by plant-based food, or the Mediterranean diet which allows moderate amounts of poultry, pork, lamb and beef.

Which diet should you choose?

Let’s start with a new fad: the climatarian diet. One version was created by the not-for-profit organization Climates Network, which says this diet is healthy, climate friendly and nature friendly. According to the publicity, “with a simple diet shift you can save a tonne of CO₂ equivalents per person per year” (“equivalents” just means methane and other greenhouse gases are factored in alongside carbon dioxide).

Meat, especially highly processed meat, has been linked to a string of major health issues including high blood pressure, heart disease and cancer.

Sounds great, but the diet still allows you to eat meat and other high-emission foods such as pork, poultry, fish, dairy products and eggs. So this is just a newer version of the “climate carnivore” diet except followers are encouraged to switch as much red meat (beef, lamb, pork, veal and venison) as possible to other meats and fish.

The diet does, however, encourage you to cut down on meat overall and to choose responsibly produced and local meat where possible, in addition to avoiding food waste and consuming seasonal, local foods.

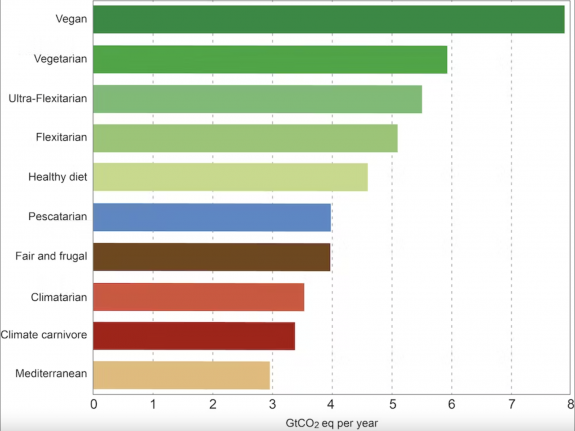

So saving a tonne of carbon dioxide is great but switching to vegetarianism or veganism can save even more. A Western standard meat-based diet produces about 7.2 kilograms of CO₂ equivalent per day, while a vegetarian diet produces 3.8 kg and a vegan diet 2.9 kg. If the whole world went vegan, it would save nearly 8 billion tonnes CO₂equivalent — while even a switch to the Mediterranean diet would still save 3 billion tonnes. That is a saving of between 20 and 60 percent of all food emissions, which are currently at 13.7 billion tonnes of CO₂equivalent a year.

Here’s how much CO2e (in billions of tonnes, or Gt) would be saved if the whole world switched to each of these diets. Terms as defined by CarbonBrief. Data: IPCC, author provided

Plant-based diets can save water and land — and they’re healthier

To save our planet, we must also consider water and land usage. Beef, for instance, needs about 15,000 liters of water per kilo to produce. Some vegetarian or vegan foods like avocados and almonds also have a huge water footprint, but overall a plant-based diet has about half the water consumption of a standard meat-based diet.

A global move away from meat would also free up a huge amount of land, since billions of animals would no longer have to be fed. Soy, for instance, is one of the world’s most common crops, yet almost 80 percent of the world’s soybeans are fed to livestock.

The reduced need for agricultural land would help stop deforestation and help protect biodiversity. The land could be used to reforest and rewild large areas, which would become a natural store of carbon dioxide.

One study suggests a move to a global plant-based diet could reduce global mortality by up to 10 percent by 2050.

What’s more, a plant-based diet is generally healthier. Meat, especially highly processed meat, has been linked to a string of major health issues, including high blood pressure, heart disease and cancer. One study suggests that a move to a global plant-based diet could reduce global mortality by up to 10 percent by 2050.

However, meat, dairy and fish are the main sources of some essential vitamins and minerals such as calcium, zinc, iodine and vitamin B12. A strict vegan diet can put people at risk of deficiencies unless they can have access to particular foods or take supplements. Yet both supplements and vegan food products are too expensive or difficult for many people around the world to access, and it would be hard to scale up supplement production to provide for billions of extra people.

So a climatarian or flexitarian approach means there are fewer health risks but it still allows people to exercise choice.

We slaughter around nine animals per person per year — even though the same nutrients can come from plants

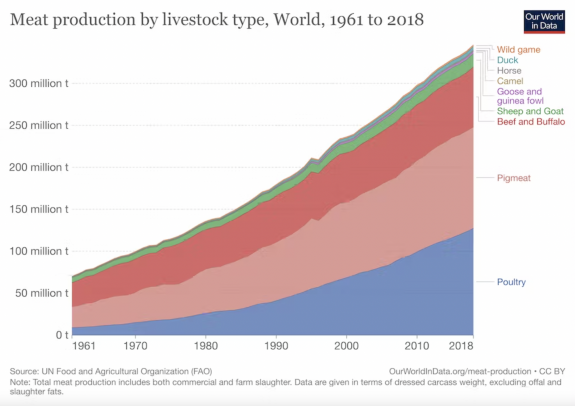

One issue that seems to be missing from many food discussions is the ethical dimension. Every year we slaughter 69 billion chickens, 1.5 billion pigs, 0.65 billion turkeys, 0.57 billion sheep, 0.45 billion goats and 0.3 billion cattle for food worldwide. That is over nine animals killed for every person on the planet per year — all for the nutrition and protein that we know can come from a plant-based diet.

Poultry production has almost doubled this century, as chicken has raced ahead of pork and beef. Our World In Data / data: FAO, CC BY-SA

So what is the ideal global diet to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, reduce habitat destruction and help you live longer?

Well, I suggest being an “ultra-flexitarian,” a diet of mostly plant-based foods but one that allows meat and dairy products in extreme moderation, with red and processed meat completely banned. This would save at least 5.5 billion tonnes of CO₂ equivalent per year (or 40 percent of all food emissions), decrease global mortality by 10 percent, and prevent the slaughter of billions of animals.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Watch these TED-Ed videos to learn more about how our diets and food production affect the planet:

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Mark Maslin PhD is a Professor of Earth System Science at University College London and the Natural History Museum of Denmark. He is a co-founder of the leading AI geospatial analytics company Rezatec Ltd and he was a Royal Society Industrial Fellow. He is science advisor to Transition Lab, Sopra-Steria, Net Zero Now, and Sheep Inc. He is member of Cheltenham Science Festival Advisory Committee. Maslin is a leading scientist with particular expertise in past and future global and regional climatic change and has publish over 185 papers in journals such as Science, Nature, Nature Climate Change, The Lancet and Geology. He has been awarded research council, charity and Government research and postgraduate training grants of over £75 million. Professor Maslin has presented over 50 public talks over the last three years for example: Twitter (EU/Asia), New Scientist Live, Guardian ‘Master Classes’, Google (UK), Global Leaders Forum (South Korea), RGS, Royal Society, Edinburgh International Book Festival, Hay literature festival, Harvard, Edinburgh, Oxford and Cambridge Universities etc. He has supervised 15 Research fellows, 20 PhD students and over 60 MSc students. He has also have written 10 popular books, over 80 popular articles (e.g., The Conversation, New Scientist, Geographical magazine, The Times, Independent and Guardian), appeared on radio and television (including Timeteam, Newsnight, Dispatches, Horizon, The Today Programme, Briefing Room, BBC News, Channel 5 News, and Sky News). He was also one of the key presenters of Sir David Attenborough’s BBC One ‘Climate Change: The Facts’. His books include the high successful ‘Climate Change: A Very Short Introduction’ (OUP, 2021), ‘The Cradle of Humanity’ (OUP, 2019), ‘The Human Planet: How we created the Anthropocene’ co-authored with Simon Lewis (Penguin, 2018) and ‘How to save our planet: the facts’ (Penguin, 2021). Maslin was also a co-author of the 2009 Lancet report ‘Managing the health effects of climate change’ and a contributor the annual Lancet Commission on climate change and global health. Prof. Maslin was included in Who’s Who for the first time in 2009 and was granted a Royal Society Wolfson Research Merit Award for the study of early human evolution in East Africa in 2011. He is currently the Co-Director of the London NERC Doctoral Training Partnership.

![]()