MLK’s ‘beloved community’ has inspired social justice work for decades − what did he mean?

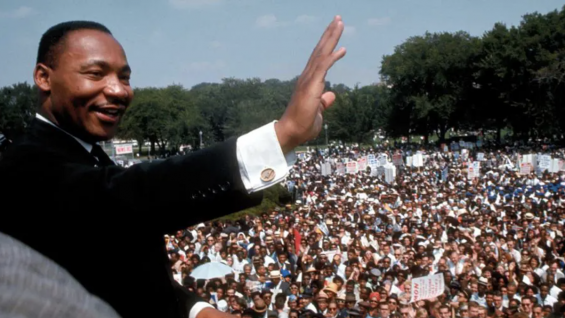

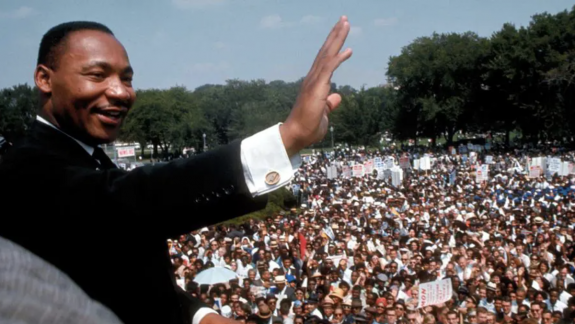

Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom 1963; Francis Miller/Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images

Since 1983, when President Ronald Reagan signed Martin Luther King Jr. Day into law, many Americans have observed the federal holiday to commemorate the life and legacy of the civil rights leader, Baptist minister and theologian.

MLK Day volunteers typically perform community service that continues King’s fight to end racial discrimination and economic injustice – to build the “beloved community,” as he often said.

King does not fully explain the phrase’s meaning in his published writings, speeches and sermons. Scholars Rufus Burrow Jr. and Lewis V. Baldwin, however, argue that the beloved community is King’s principal ethical goal, guiding the struggle against what he called the “three evils of American society”: racism, economic exploitation and militarism.

As a Baptist minister and theologian myself, I believe it is important to understand the origins of the concept of the beloved community, how King understood it and how he worked to make it a reality.

Older origins

Although King popularized the beloved community, the phrase has roots in the thought of 19th-century American religious philosopher Josiah Royce.

In 1913, toward the end of his long career, Royce published “The Problem of Christianity.” The book compiles lectures on the Christian religion, including the idea of the church and its mission, and coined the term beloved community. Based on his readings of the biblical gospels, as well as the writings of the apostle Paul, Royce argued that the beloved community was one where individuals are transformed by God’s love.

In turn, members express that love as loyalty toward each other – for example, the devoted love a member of the church would have toward the church as a whole.

While Royce often identified the beloved community with the church, he extends the concept beyond the walls of Christianity. In any type of community, Royce argued, from clans to nations, there are individuals who express love and devotion not only to their own community, but who foster a sense of the community that includes all humankind.

According to Royce, the ideal or beloved community is a “universal community” – one to which all human beings belong or will eventually belong at the end of time.

‘Beloved’ diversity

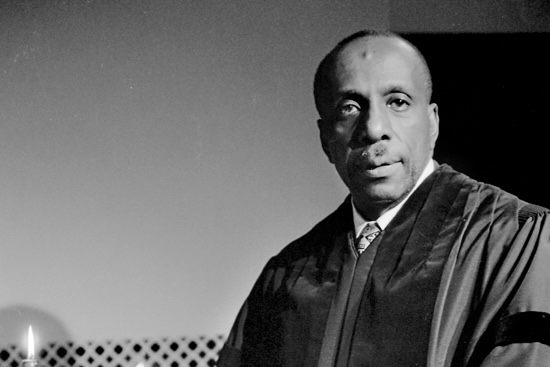

Twentieth-century pastor, philosopher, mystic, theologian and civil rights leader Howard Thurman retrieved Royce’s idea of the beloved community and applied it to his life and work, most notably in his 1971 book “The Search for Common Ground.”

Thurman first used the term in an unpublished and undated article: Desegregation, Integration, and the Beloved Community. Here, he argued that the beloved community cannot be achieved by sheer will or commanded by force. Rather, it begins with transformation in each person’s “human spirit.” The seeds of the beloved community extend outward into society as each person assumes the responsibility of bringing it to pass.

Thurman envisioned the beloved community as one that exemplifies harmony – harmony enriched by members’ diversity. It is a community wherein people from all racial, national, religious and ethnic backgrounds are respected, and where their human dignity is affirmed. Thurman was convinced that beloved community was achievable because of the dedication he saw from activists during the struggle for racial integration.

During his lifetime, Thurman sought to build this beloved community through his activism for racial justice. For example, he co-founded the Church for the Fellowship of All Peoples, an interracial and interfaith community in San Francisco, which he co-pastored from 1943 to 1953.

Thurman’s writings and activism deeply influenced King. Burrow argued that it is not entirely clear when and where King first learned the concept of beloved community. Yet King emphasized its importance in much of his writing and political action.

Love and action

In simplest terms, King defined the beloved community as a community transformed by love. Like Royce, he drew his understanding of love from the Bible’s New Testament. In the original Greek, the Gospels use the word “agape,” which suggests God’s self-giving, unconditional love for humanity – and, by extension, human beings’ self-giving, unconditional love for each other.

According to Baldwin, however, King’s understanding of the beloved community is better understood against the backdrop of the Black church tradition. Raised in the Ebenezer Baptist Church of Atlanta, King learned lessons on the meaning of love from his parents, Rev. Martin Luther King Sr. – Ebenezer’s pastor, who was also a leader in the local chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People – and Alberta Christine Williams King.

One of the distinctions in King’s thought is that he believed the beloved community could be achieved through nonviolent direct action, such as sit-ins, marches and boycotts. In part, he was inspired by Thurman, who had embraced the nonviolence at the heart of Mahatma Gandhi’s resistance against the British in India. For King, nonviolence was the only viable means for achieving the United States of America’s redemption from the sin of racial segregation and white supremacy.

Martin Luther King Jr. and his wife, Coretta, lead a five-day march to the Alabama State Capitol in Montgomery in 1965. Bettmann via Getty Images

For King, therefore, the beloved community was not merely a utopian vision of the future. He envisioned it as an obtainable ethical goal that all human beings must work collectively toward achieving.

“Only a refusal to hate or kill can put an end to the chain of violence in the world and lead us toward a community where men can live together without fear,” King wrote in 1966. “Our goal is to create a beloved community and this will require a qualitative change in our souls as well as a quantitative change in our lives.”

…

Searching for the beloved community today

King’s idea of the beloved community has not only influenced people affiliated with the Christian tradition but also people from other faiths and none.

For instance, scholars Elizabeth A. Johnson, bell hooks and Joy James have reflected upon the meaning of the beloved community amid ongoing challenges such as global climate change, sexism, racism and other forms of structural violence.

People around the world continue to draw insight and inspiration from King’s thought, especially from his insistence that love is “the most durable power” to change the world for the better. Questions remain about whether his beloved community can be realized, or how. But I believe it is important to understand King’s ethical concept and its continuing influence on movements that seek an end to injustice.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Jason Oliver Evans is a postdoctoral research associate and lecturer at the University of Virginia. Evans is a constructive theologian working at the intersection of Christian systematic theology with theological and social ethics, Africana studies, and studies of gender and sexuality.

Evans earned a Master of Arts and a Ph.D. in religious studies from the University of Virginia, a Master of Theology from Candler School of Theology at Emory University, a Master of Divinity from Duke University Divinity School, and a Bachelor of Science in speech communication from Millersville University of Pennsylvania (2008). An ordained minister in the American Baptist Churches USA, Inc., Evans currently serves as an associate minister at the historic St. Paul’s Baptist Church in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Evans enjoys cooking, baking, reading cookbooks and food magazines, and binge-watching cooking shows in his spare time.

![]()