Why you should always thank your barista

Writer A.J. Jacobs was going through life feeling more grumpy than grateful. To start cultivating a thankful attitude, he decided to show some appreciation to the people behind his daily cup of coffee. Here’s what he discovered when he met his barista.

Gratitude is not an emotion that comes naturally to me. My innate disposition is moderately grumpy, more Larry David than Tom Hanks. But I’ve read enough about gratitude to know it’s one of the keys to a life well lived. Perhaps even, as Cicero says, it is the chief of virtues.

According to the research, gratitude’s psychological benefits are legion: It can lift depression, help you sleep, improve your diet, and make you more likely to exercise. Heart patients recover more quickly when they keep a gratitude journal. A recent study showed gratitude causes people to be more generous and kinder to strangers. Another study found that gratitude is the single best predictor of well-being and good relationships, beating out twenty-four other impressive traits such as hope, love, and creativity. As the Benedictine monk David Steindl-Rast (TED talk: Want to be happy? Be grateful) says, “Happiness does not lead to gratitude. Gratitude leads to happiness.”

For a while now I’ve made modest efforts to kick-start my gratitude whenever I could and to instill the value in my kids. My three boys are required to write handwritten thank-you notes when they get birthday gifts, much to their disbelief.

Sometimes, before a meal, I’ll say a prayer of thanksgiving. Sort of. I’m agnostic, so instead of thanking God, I’ll occasionally start a meal by thanking a handful of people who helped get our food to the plate. I’ll say, “Thank you to the farmer who grew the carrots, to the truck driver who hauled them, to the cashier at Gristedes grocery store who rang me up.”

“You know these people can’t hear you, right?” my son Zane asked me one night.

I told him I knew, but that it’s still good to remind ourselves of others’ contributions.

Yet Zane’s comment stayed with me. I wondered if I should commit more fully. What would it be like to personally thank those who helped make my food? Each one of them?

“In my default mode, I’m mildly to severely aggravated more than 50 percent of my waking hours. That’s a ridiculous way to go through life.”

I knew the idea was absurd — and that I could attempt it only because I make my living doing absurd things and writing about them. It’d be a major headache. It’d be time-consuming and travel-heavy. But it could also have huge benefits. It might be a nice thing for the people who make my meals possible. It would show my sons I’m serious about gratitude, and they should be too.

And it might make me more grateful, which would, in turn, make me less petty and annoyed. Because I needed to be less annoyed. Even though I know that I’m ridiculously lucky — I don’t lack for meals and I have a job that I mostly enjoy — I still let all the daily irritations hijack my brain. I’ll step on our dog’s dinosaur-shaped chew toy, or I’ll open an email that begins, “Dearest A.J., I regret to inform you . . . ,” and I’ll forget the hundreds of things that go right every day and focus on the three or four that go wrong.

In my default mode, I’m mildly to severely aggravated more than 50 percent of my waking hours. That’s a ridiculous way to go through life. I don’t want to get to heaven (if such a thing exists) and spend my time complaining about the volume of the harp music.

I needed a mental makeover, and a gratitude project could be my key to success. My goal for this project was to flip my ratio: By the end, I wanted to spend more than half of my average day experiencing gratitude and mild happiness. Or at least not outright irritation.

My first task: I had to choose what food item to be thankful for. I considered apples, white wine and Monterey jack cheese. I thought about nonfood items as well: my pen, my socks, my toothpaste. Almost every object I encounter in my day requires thousands of humans and tons of effort — effort I take totally for granted.

Finally, I settled on something I can’t live without: my coffee. It seemed right for a couple of reasons. I do love my morning cup from my local café. I take it to go, no milk. I’m not a fanatic and my palate is unrefined, but I relish coffee’s bitter taste and the pleasant buzz it gives me — it’s my favorite narcotic, hands down.

Also, coffee has a huge impact on our world. More than two billion cups of coffee are drunk every day around the globe. The coffee industry employs 125 million people internationally. Over the centuries, coffee has helped create international trade and shape our modern economy.

“The act of noticing, after all, is a crucial part of gratitude; you can’t be grateful if your attention is scattered.”

So I set out on the Great Coffee Gratitude Trail, intent on following all its twists and turns. I decided to do this project in reverse, starting with my local café and working my way backward to the birth of the coffee. My coffee shop, Joe’s Coffee, is a block’s walk from my apartment.

On a Thursday morning, I get in line, prepping myself to say the very first “thank you” of Project Gratitude. While waiting, I force myself to stash my smartphone in my pocket and actually notice my surroundings. The act of noticing, after all, is a crucial part of gratitude; you can’t be grateful if your attention is scattered.

There are moms pushing strollers, dogs tied up outside, the frequent hiss of the espresso machine. Glowing indigo lamps hang from the ceiling. That indigo light is lovely, I think to myself. I get to the counter and am greeted by my barista, a twenty-something woman with hair gathered in a ponytail atop her head. She hands me my order — a small black coffee, the daily blend.

“Thank you for my coffee,” I say.

“You’re welcome!” she says, smiling.

And there it is — my first thank you. It’s fine, but no lightning bolts yet. I slide my credit card to pay the three-dollar fee. (Three dollars is, of course, ridiculously expensive. But in a weird sense, as I later learned, it’s also wildly underpriced.)

A couple of days later, I’ve worked up the nerve to tell the barista about Project Gratitude. I asked her if she’d be willing to share with me a bit about what goes into making my coffee. She said she’d be happy to talk after her shift.

“Thanks again for the coffee,” I say, as we sit down at one of Joe’s small tables.

“Thanks for thanking me,” she says.

I consider thanking her for thanking me for thanking her, but decide to cut it off lest we get caught in an infinite loop. She tells me her name is Chung. Her parents are Korean immigrants, and she grew up in Southern California before moving to New York City for college.

“Chung, a barista, has been snapped at by a bratty nine-year-old girl who didn’t like the milk-foam design on top of her hot chocolate.”

“So . . . ,” I say. “Um . . . What’s it’s like being a barista?”

“It’s not always easy,” she says.

This is because you’re dealing with people in a very dangerous condition: pre-caffeination. Chung tells me tales of customers who refuse to even make eye contact. They just snarl their order and thrust out their credit card. She’s had customers berate her till she cried for mixing up orders (which she swears she didn’t). She’s been snapped at by a bratty nine-year-old girl who didn’t like the milk-foam design that Chung created on top of her hot chocolate. Chung made a teddy bear. The girl wanted a heart. “I wanted to tell her that she did need a heart—a real one.”

Yet Chung says the cranky customers are the minority. Most folks are friendly, especially when she sets the mood by being friendly first. And man, Chung is friendly. She is a smiler and a hugger. She’s like a morning-show host, but not forced or fake. During our half-hour chat, Chung got up no fewer than five times to hug longtime customers and former coworkers.

“I first realized I might be good at customer service when I was working as an usher at my church,” she says. “I saw that it takes a certain personality.”

And, like at church, when she’s at Joe Coffee, she sometimes watches as people are transformed, their faces lighting up when they get their cups.

“I see my job as getting them coffee, but also making them happy,” she tells me.

I ask her if she’s planning on being a barista for the long haul.

She shakes her head. “Actually, this is my last week.”

She’s moving back to California to take care of her parents. Plus, nowadays, she’s having trouble staying up on her feet her entire shift.

“Let me give you a visual of why,” Chung says.

She takes out her smartphone and swipes to a photo. It’s a startling image of her left foot, bloody, bruised, and with more than a dozen metal pins sticking out of it.

“A year and a half ago, I got hit by a bus,” she says. “I broke every toe, the heel, the ankle. The skin was gone.”

“Oh my God.”

“Yeah, it wasn’t pretty.”

“On my way home, I make a pledge. I promise to look baristas in the eyes — because I know I’ve been that jerk who thrusts out the credit card without glancing up.”

Chung says it’ll be sad to leave the regulars. She talks about Nancy and John, who arrive every morning as soon as the glass door is unlocked. “I always say, ‘How’s your day going?’ And John will say, ‘Now it’s going well.’” She’ll miss her coworkers, whom she says always have her back.

She won’t miss the occasional feeling that she doesn’t exist at all. “What’s upsetting is when people treat us like machines, not humans,” Chung says. “When they look at us as just a means to an end — or don’t even look at us at all.”

I thank Chung, and she gives me a hug (her 11th of the day, by my estimate).

On my way home, I make a pledge. Though I probably won’t hug any other baristas, I promise to look them in the eyes — because I know I’ve been that asshole who thrusts out the credit card without glancing up. I’m not sure if I ever did it to Chung, but I know I’ve treated many others — waiters, delivery people, bodega cashiers — as if they were vending machines.

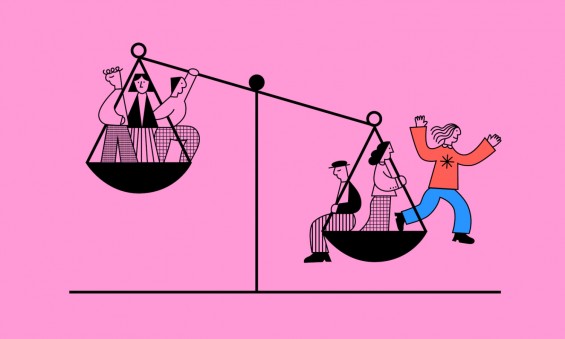

I sometimes wear these noise-cancelling headphones when running errands, so that just makes me look more aloof and unfriendly. And this is an enemy of gratitude. UC Davis psychology professor Robert Emmons — who is considered the father of gratitude research — puts it this way: “Grateful living is possible only when we realize that other people and agents do things for us that we cannot do for ourselves. Gratitude emerges from two stages of information processing — affirmation and recognition. We affirm the good and credit others with bringing it about. In gratitude, we recognize that the source of goodness is outside of ourselves.”

From now on, when I have an interaction with anyone else, I’ll try to affirm and recognize them. I’ll try to remember to treat them as humans — at least until robots take over all service jobs. I’ll try to keep in mind that they have families and favorite movies and embarrassing teenage memories and possibly aching feet.

Excerpted from the new book Thanks A Thousand!: A Gratitude Journey by A.J. Jacobs. Reprinted with permission from TED Books/Simon & Schuster. © 2018 A.J. Jacobs.

Watch A.J. Jacob’s TED talk here:

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

A.J. Jacobs is the author of the New York Times bestsellers “The Know-It-All”, “The Year of Living Biblically” and “Drop Dead Healthy”, among other books. He is a contributor to NPR and Esquire magazine, and he has written for The New York Times and The Washington Post. This piece was adapted for TED-Ed from this Ideas article.