10 incredible women in history you should know

A few years ago, I began to notice that the people I taught about in my World History classes were, more often than not, European men.

When women were included in the state curriculum, they felt like token inclusions who were often related to men and discussed in proximity to them; not as independent actors. They were often queens or empresses, and only a few women of “normal” status made our lessons. I began the work of analyzing my World History lessons to make them more inclusive and diverse. I found that by including women with different backgrounds, fields, and from different parts of the world, I could provide students with role models they could identify with, and remind male students that women are capable of greatness too.

Here’s some additional good news: we don’t need to carve out a single month, special lesson, or unit, to incorporate women into our lessons. First, when planning, I ensure that I include women next to their male colleagues in all my materials. Then, when executing the lessons, I tell these women’s stories in as well-rounded a way as possible because it’s not just who we teach about— it’s how we approach their story that can give it power.

For example, when I teach about Cleopatra, I don’t just talk about her in relation to Julius Caesar or Marc Antony— I spend time discussing how she was a linguist, and the first Greek of the Ptolemaic line ruling Egypt who learned to speak Egyptian; she was a scholar and a woman who understood her people. When I teach about women like the Empress Josephine or Marie Antoinette, I discuss their emotions, letters, relationships, and struggles in unhappy marriages.

In all narratives that we share, male and female alike, we have the opportunity to humanize history, to make people on pages relatable by talking about their emotions, their mental health, and their experiences. When we bring them to life for students, we draw students into history.

I polled my students, past and present, to ask them which figures they remember most, and I have included some of their favorites as well my own. Here are 10 amazing women you should know and share, from the 300s CE to the 1900s CE:

1. Hypatia (c. 370 CE – March 415 CE) – Ancient Rome

Hypatia of Alexandria was a philosopher, mathematician, and teacher, born in Alexandria, Egypt around 370 CE, just before Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire. She was the daughter of a mathematician who taught her math and astronomy, and trained her in Neo-Platonic philosophy. She joined her father as a teacher at the University of Alexandria, and was a beloved teacher who fostered an open environment, teaching pagans, Jews, and Christians.

Both her presence as a female teacher and her insistence on an accepting classroom in an increasingly hostile religious atmosphere of early Christian Rome made her courses unusual and that much more coveted. She was widely known for her love of learning and expertise, but in 415 CE, due to her high profile and power as a non-Christian woman, she was targeted by a mob of Christian monks who killed her in the streets. They then also burned the University of Alexandria, forcing the artists, philosophers, and intellectuals to flee the city. Hypatia’s life models open-mindedness, generosity, and a love of learning, and her death is often discussed as a watershed turning point in the Classical world.

Topics you can connect her to in history include the connections between Roman and Greek philosophy, and the rise of Christianity in the Roman Empire. Students have loved learning about a woman who taught in such an open-minded way, and learning she is one of my role models too.

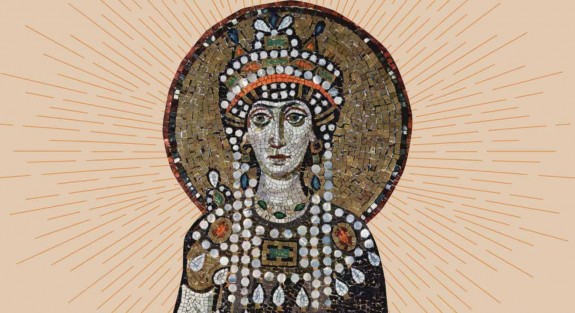

2. Empress Theodora (c. 497 – c. 548) – The Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empress Theodora was born into a circus family in Constantinople, just after the fall of the Western Roman Empire. Her father likely worked as a bear trainer in the Hippodrome, and a young Theodora, it was said, took work as an actress and dancer. The Byzantine Emperor Justinian encountered her one day and, taken by her beauty, determined to marry her. However, because she was a commoner and had a bit of a reputation, special laws had to be passed in order for them to marry.

Though she never technically co-ruled the empire with Justinian, she had significant influence and power, and was a trusted advisor who promoted religious and social policies, many of which benefited women. Some of which included altering divorce laws and prohibiting the traffic of young women. Her name was listed in nearly all laws passed, she had regular communication with other foreign rulers, and received foreign envoys. Empress Theodora is credited with helping stabilize Justinian’s power after she urged him to stand his ground during the Nika revolt of 532 CE.

Topics you can connect her to in history include the Byzantine Empire, naturally, and students have told me they love her backstory and how she fought for women’s rights. They also enjoy how she pushed Justinian to make him a better ruler.

3. Sappho of Lesbos (c. 620 – c. 570 BCE) – Ancient Greece

Sappho of Lesbos was a lyric poet of Ancient Greece who was so famous during her life that statues were created in her honor. She was praised by Plato and other Greek writers, and her peers referred to her as the “Tenth Muse” and “The Poetess.” Very few fragments of her work survived because she wrote in a very specific dialect, Aeolic Greek, which was difficult for later Latin writers to translate.

Her poetry was lyric poetry – to be accompanied by the lyre – and was sung frequently at the parties of high-ranking Greeks. She wrote about passion, loss, and deep human emotions. Some of her surviving poems imply she may have had romantic relationships with women, and thus from her name we get the etymology of “lesbians” and “sapphic.”

Topics you can connect her to in history include the ancient Greeks and Greek philosophy and art. Every year, I have female students who have told me that they valued her inclusion because it was the first time they had heard about an LGBTQ+ person in their history class, and the representation meant so much to them.

4. Margery Kempe (c. 1373 – c. 1440 CE) – Middle Ages Europe

Margery Kempe was an English mystic and traveler, and is also the author of the first autobiography in the English language. She was the mother to 14 children. After her first child was born, Margery had a traumatic postpartum experience of a form of psychosis; for months she was catatonic, experiencing visions, and was tied to her bed for her own safety. For the rest of her life she would experience these visions, and later on she would leave her family and travel on pilgrimages to Spain, Jerusalem, Rome, and Germany.

Margery was known to weep loudly at various shrines and this behavior did not endear her to leaders in the church. She also insisted on wearing white like a nun, seeking specific permission to do so. She narrated her life and travels upon her return to two clerks who wrote it down on her behalf, so it is a unique book in that it shares her very specific life experiences in her own voice. Margery is a conflicting person to teach about because of her mysticism: do we discuss her experiences and travels through the lens of religion, or mental health? Historians often opt for both, as we seek to understand her contributions and life.

Topics you can connect her to in history include Christianity, the Middle Ages in Europe, and travel narratives like those of Marco Polo and Ibn Battuta. My students remember Margery fondly, and she makes their list of favorites consistently. They like how we talk about her through the lens of mental health and that she pursued what she believed despite naysayers.

5. Njinga of Ndongo and Matamba (c. 1581 – c. 1663 CE) – Post-Classical Africa

Njinga Mbandi was a warrior queen of modern Angola. She was born to a concubine of the king of Ndongo and as a daughter, it was unlikely she would take the throne, so her father allowed her to attend many of his important meetings and negotiations, and also allowed her to be trained as a warrior and educated fully. When her half-brother took the throne after their father’s death, he had her infant son killed and Njinga fled to nearby Matamba, but returned when her brother begged her to negotiate on behalf of her people with the rapidly encroaching Portuguese. Njinga did so successfully, due to her notably diplomatic skills and her insistence on respect from the Portuguese, going so far as to refuse to sit lower than them during the negotiations. She won significant concessions from the Portuguese.

When her brother died, Njinga took the throne; at various points during her reign, Njinga was deposed, regained power, lost territory, and gained it. She struggled against the Portuguese to maintain her peoples’ independence. Ultimately, when Njinga died at the age of 81, she left behind a stable kingdom that would be led by women for the majority of the next 100 years. While Ndongo was eventually taken by the Portuguese, Matamba maintained its independence through the 1900s.

Topics you can connect her to in history include Africa and the age of European exploration, as well as African resistance to Europeans. I think it’s important that we show examples of successful resistance and a powerful legacy.

6. Artemisia Gentileschi (c. 1593 – c. 1654) – Renaissance Europe

Artemisia Gentileschi was born in Rome to a gifted painter. Her father trained her to paint and even hired a tutor for her; ultimately this ended in tragedy, as the tutor raped Artemisia. There was a horrific trial and Artemisia was tortured with thumbscrews for “the truth.” Artemisia left for Florence, had a family, and was the first woman to gain membership to the Academy of the Arts of Drawing. She went back to paint in Rome for a time, as well as London where she painted in the court of Charles I, and then settled in Naples.

While in Florence, she painted for Michelangelo the Younger in the Casa Buonoratti, and was paid more than her male peers for her time and efforts. Artemisia’s work is profound, passionate, unabashed, and reclaims the space of women in the stories told about them. She makes women her focal points, her heroines, and paints them in positions of strength, and often revenge.

A topic you can connect her to in history is of course the Renaissance. Artemisia has stuck for many of my female students who have experienced sexual assault or harassment. They have expressed to me that they are inspired by her strength and find solace in her paintings. One of my students even went on to do her senior capstone all about Artemisia, two years after taking my class.

7. Malintzin/Malinche/Doña Marina (c. 1500 – c. 1550) – Colonial Americas

Born to a local chieftain in Central America and a mother whose family ruled a nearby village, Malintzin (or Malinali, or Malinche) was of high rank on both sides of her family. When her father died and her mother remarried, she was secretly sold into slavery so her brother would inherit the land that was her birthright. Malintzin was sold to several tribes, and over the course of her life would learn to speak Maya, Nahuatl, and later Spanish.

She was eventually given to Hernán Cortés and his men in 1519, and upon realizing her skill as a translator, Cortes came to rely on her. Malinztin was baptised as Doña Marina, and traveled with the Spanish for the next few years as they battled or negotiated with various Indigenous groups in the Aztec Empire. She provided cultural context and insight as well as communication skills. Without her, Spanish success in the region would have been difficult to achieve. By 1521, Cortes had conquered the Aztecs and needed her to help him govern. She was given several pieces of land around Mexico City as a reward.

Topics you can connect her to in history include Spanish conquest of the Americas and Indigenous peoples of the Americas. We talk about her complicated legacy as she is viewed by some as a traitor to her people, and to others as a woman who was enslaved and did the best she could to survive in difficult circumstances. My students typically find her a fascinating and sympathetic figure, a woman who did all she could to survive and thrive in adversity.

8. Olympe de Gouges (May 7, 1748 – November 3, 1793) – Enlightenment Europe

Olympe de Gouges, born Marie Gouze, was a political activist and writer during the French Revolution. Married off against her will at the young age of 16, she renamed herself Olympe de Gouges after her husband’s death and moved to Paris. She pursued her education there and rose to a high status in Parisian society. She would host salons for thinkers of the time and would write poetry, plays, and political pamphlets. De Gouges was a pacifist, an abolitionist, and wanted an end to the death penalty. She wanted a tax plan that allowed wealth to be spread more evenly, with welfare for the less fortunate and protections for women and children.

De Gouges was in favor of the French Revolution, but when the Revolution failed to provide the equality it claimed it would, she grew critical. The Revolution was in many ways built on the backs of women: women were some of the first to march against the king and take up arms and they served on the front lines of France’s battles against other European powers. Yet women were not being provided the true “egalite” promised in terms of rights as citizens.

De Gouges wrote her most famous work in response to this, “The Declaration of the Rights of Women” (1791). It was a direct play on The Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen that was part of the first French Constitution. She became increasingly vocal, and in 1793 she was arrested by the revolutionary government and guillotined.

Topics you can connect with Olympe de Gouges, as well as Mary Wollstonecraft, include Enlightenment writers and the Age of Revolutions; it is unfair for Voltaire and Montesquieu to get all the limelight! Her ideas resonate for my students as being very modern, and they appreciate that she never backed down from her convictions and is a model of courage.

9. Manuela Sáenz (December 27, 1797–November 23, 1856) – Revolutionary Americas

Manuela Sáenz is the illegitimate daughter of a Spanish military officer and an Ecuadorian noblewoman. Her childhood included a traditional education in a convent, as well as learning how to ride and shoot. When she was 17, her father arranged her marriage to an English doctor who was nearly twice her age, James Thorne. She moved with him to Lima, Peru, where she was connected with revolutionaries who were interested in overthrowing the Spanish in Latin America.

She returned to Quito, Ecuador in 1822, and met the revolutionary leader Simón Bolívar. They fell in love and would occasionally live together and go on campaign together. Manuela would go into battle with Bolívar in the cavalry, and was promoted from captain to colonel; she even saved Bolívar from assassination at least twice. She was also given the Order of the Sun, the highest military honor in the revolutionary government. Upon Bolívar’s exile and death in 1830, Manuela had no resources and lived the rest of her life in a small coastal village in Peru, making money by writing letters for sailors, including Herman Melville. She died in a diphtheria outbreak and was buried in a mass grave. Her role in Latin America’s independence has only recently been recognized, and she was granted an Honorary General title in Ecuador in 2007.

Topics you can connect her to in history include Latin American revolutions and the Enlightenment. My students find her time as a soldier and spy endlessly interesting! I enjoy including women, particularly in this period, who went into battle, such as the women of France who fought in the revolutionary wars. I have female JROTC students who like knowing they are part of a long tradition.

10. Lyudmila Pavlichenko (July 12, 1916 – October 27, 1974) – World War II

Lyudmila Pavlichenko was born in Ukraine and was one of the best snipers in history. She pursued sharp shooting when in school and fought for the Red Army of the Soviet Union during World War II as a trained sniper. She soon began to rack up an impressive tally of kills, reaching 309 in just a few months on the frontline.

The German soldiers knew her by name, and she would engage in some of the most dangerous fighting, sniper seeking sniper. She was wounded four times in battle, and in 1942 she took shrapnel in her face.

She was sent to the United States to tour and drum up American support for the war effort, as the USSR and USA were allies at the time and the USSR depended on continued American engagement. She was often frustrated when asked by American journalists about issues around makeup, clothing, or hair. Finally, she spoke during a tour and said “Gentlemen. I am 25-years-old and I have killed 309 fascist occupants by now. Don’t you think, gentlemen, that you have been hiding behind my back for too long?” This was greeted by a roar of applause.

She got to know Eleanor Roosevelt during this tour and they became good friends. Upon her return to the USSR, Pavlichenko was promoted to major, awarded the Gold Star of the Hero of the Soviet Union, and received the Order of Lenin twice. She continued training other Soviet snipers, and then when the war ended, finished her education at Kiev University and became a historian and research assistant for the Soviet Navy.

Topics you can connect her to in history include World War II and the Cold War. Students adore her story: they find her sass, grit, and action movie skills endlessly fascinating.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Caitlin Tripp is a teacher and curriculum writer for Atlanta Public Schools. Born and raised in West Africa and Latin America, she loves to travel and learn more about the places she visits. She is passionate about women’s history, and in her free time enjoys snuggling up to a history documentary with her husband and their two cats.

Caitlin Tripp originally shared how to incorporate women into history lessons in her Educator Talk submitted through the TED Masterclass for Education program. To learn more about how TED Masterclass for Education inspires educators to develop their ideas into TED-style Talks, visit https://masterclass.ted.com/educator