Have you mispronounced someone’s name? Here’s what to do next

Most of us have stumbled when saying an unfamiliar name. That’s natural, but it’s what we do afterwards that really matters, says writer Gerardo Ochoa.

Do you remember being in 5th grade? I’ll never forget it — because that’s when my name was changed.

I was nine years old, and my family had just immigrated from Mexico to a small town east of Portland, Oregon. Making that change was not easy. People ate different foods, they wore different clothes, and they spoke a different language. I quickly realized that when you are different, it can be very easy for everyone around you to tell you who you should be.

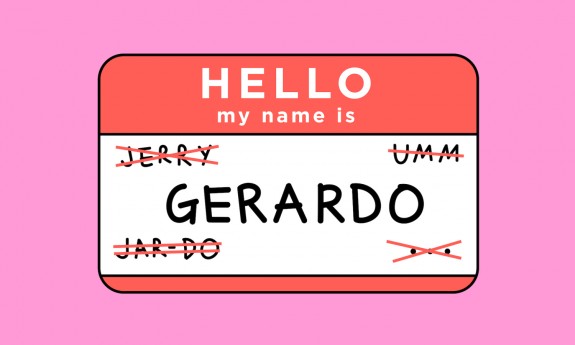

That’s when my name was changed, and I remember precisely when it happened. During the first fifth-grade roll call, the teacher started by calling out “John!” John answered in his squeaky voice: “Here.” Then, the teacher went down the list: “Kimberly!” and “Sarah!” They all called out “Here.” When she got to my name, she said, “Her … Jer … Jerry …” She settled on “Jerry!” (For the record, my name is pronounced “Her-are-doe”).

Without realizing it, she not only changed my name but my life. Because I was still learning to speak English and my parents had taught me to respect my teachers and elders, I didn’t question it. What I wanted to do was fit in. But fitting in came with a price.

Before long, few people knew my real name. It was like an out-of-control wildfire that spread too far, too fast for me to stop it. I accepted my new name, but I knew it was not me. I felt ashamed, I felt dirty, and I felt like a fraud. This wrong name was everywhere — in the school yearbook, my school ID, the local newspaper. Don’t get me wrong: I actually like the name Jerry. The only problem I had with it is it was not my name.

By now, I’ve heard thousands of variations of my name from students, teachers, employers, strangers who’ve become friends, and strangers who’ve remained strangers. I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about this, I’ve researched it, and I’ve reflected on it.

Educator and podcaster Jennifer Gonzalez has done a fantastic job on this subject, and she has come up with three different categories of mispronouncers, which I’d like to describe and build upon. Most of us have been one of them, at one time or another:

The Fumble Mumbler

When I meet a fumble mumbler and introduce myself, they typically get nervous. They attempt to say my name, struggle a bit in the process, and may giggle. They usually settle for some close approximation of my name. I really don’t mind the fumble mumblers, because I can see that they’re trying and they know their problem is with their mispronunciation and not with my name.

The Arrogant Mangler

When I meet a mangler, I know right away what kind of relationship we’ll have — and it’s usually not a good one. When I introduce myself, the arrogant mangler will respond with “Geraldo, it’s great to meet you blah blah blah …” They’ll go on talking, completely oblivious to the fact that they mispronounced my name. Often, they will continue with their own version of my name — even after I correct them. I have very little patience for the arrogant mangler, because to me they’re showing great disrespect or they don’t even care to try pronouncing my name.

The Calibrator

These are my favorite group of mispronouncers. The calibrator will listen to my name, they’ll slow down, read my lips, and attempt to say it. They may get it wrong, but they try again and again until they get it. Sometimes, they’ll come back to me the next day or week to ensure they’ve still got it right. If you struggle to pronounce some names, always strive to be a calibrator.

The Evader

I’d like to add a fourth category to Gonzalez’ list: the evader. These are the people who’d rather call me something different than call me by my name or look silly trying to pronounce it. When I introduce myself, they say things like “Do you have a nickname?” or “I’m never going to be able to say that!” or “Can I just call you G or Jerry?” No matter what they say, it ends up making me feel like an other, like I don’t belong.

Pronouncing someone’s name correctly can make people feel valued, honored and respected — and mispronouncing their name creates real problems. Carmen Fariña, former chancellor of the New York City school system, has spoken about how she was marked absent for six weeks in kindergarten because she never heard her name being called. As it turns out, her name was read but it had been anglicized and mispronounced. Mispronouncing someone’s name leads to invisibility, and when students feel invisible in the classroom, she argues, they are less likely to have academic success.

Mispronouncing someone’s name can even have financial costs. In the 2013 offseason, basketball superstar Stephen Curry — pronounced Steff-en — switched sneaker sponsors, going from Nike to Under Armour. Why? According to an ESPN article that quoted Curry’s father, during Nike’s marketing pitch a couple of executives referred to Stephen as “Steph-on” (with an incorrect emphasis on the second syllable). This and a few other blunders cost Nike the support of an iconic player — and is estimated to have driven some $14 billion in sales to Under Armour.

Why is pronouncing someone’s name correctly such a struggle? When I talked to Nancy, my wife, about this, she shared her thoughts in a way that made a lot of sense. She said, “It’s kind of like driving. Some people have been privileged their entire life driving an automatic; when they meet you, you’re asking them to learn how to drive a stick-shift quickly on the spot. Some people can do it, others are willing to try, and some simply refuse.”

Every time I share the story about my name, I’m comforted by the fact that I’m not alone. So many people have had experiences similar to mine. At the same time, I’m disturbed that most people in the US who connect with it are immigrants and people of color. As our communities continue to be more diversified and globalized, the likelihood we’ll meet someone whose name we can’t pronounce keeps increasing.

All of us, myself included, are going to stumble and fumble. But it’s not your mistake that matters most; it’s what you do after the mistake. That’s when you have the chance to make someone feel like they belong — or feel like they’re the other. What will you choose to do?

Here are three simple tips that have helped me navigate this area:

Be humble — admit when you’re having difficulty with a name.

The first step to pronouncing someone’s name correctly is to acknowledge to yourself that you can’t pronounce it. It’s okay if the other person sees you struggling, and it’s okay if you have to ask for help. Usually, they’ll be more than willing to assist. When I see someone struggling to say my name, I help them, so when they finally achieve success, their success is my success, too. We both win.

Be an active bystander.

When you see and hear someone mispronounce another person’s name, take the initiative and correct them. So far, this has just happened once in entire life, and I’ll never forget it. When a friend corrected somebody else’s mispronunciation of my name, it took the burden off me. Deep down, it made my heart smile.

Don’t ever change someone’s name just because you can’t say it.

Try saying someone’s name, even if you get it wrong. Changing someone’s name is a decision that belongs to that individual, not to you.

I work on a college campus, and my favorite time of year is commencement, when we read graduating students’ names out loud. I’m fortunate to work with colleagues who practice and take great care with their pronunciation. It’s not lost on us that many people have spent so much time and given up so much — particularly immigrants who’ve have left their entire lives behind — to witness that moment when their student takes the stage. Those diplomas are more than pieces of paper. They symbolize sacrifice, hard work and sleepless nights, and people should hear their names pronounced correctly.

Let’s face it: We’re not always going to get people’s names right. But, more than ever, it matters that we try.

This piece has been adapted from his TEDxMcMinnville talk. Watch it here:

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Gerardo Ochoa is a first-generation college graduate and Latinx immigrant, who has dedicated his career to promoting college affordability, access, and graduation. He believes in the power of personal stories to build empathy, create opportunities, and influence change. He is director of community relations at Linfield College in McMinnville, Oregon. You can follow him on twitter: @gerardoochoa

This post was originally published on TED Ideas. It’s part of the “How to Be a Better Human” series, each of which contains a piece of helpful advice from someone in the TED community; browse through all the posts here.