How to raise kids who will grow into secure, trustworthy adults

If kids don’t feel trusted — or if there isn’t anyone close to them whom they can rely on — they can really suffer. Esther Wojcicki, an educator and mother of three superstar daughters, explains why trust is essential and how to build it in the young people in our lives.

Esther Wojcicki has inspired thousands of kids through her 35-year-and-counting career as a journalism and English teacher at Palo Alto High School in California. She and her husband, Stanley, have also raised three exceptionally accomplished daughters: Susan (YouTube CEO), Janet, a Fulbright-winning anthropologist, pediatrics professor and researcher), and Anne (cofounder and CEO of 23andMe). So she knows quite a bit about helping young people grow into great grown-ups. Here, she writes about the critical importance of trust and how to cultivate it in children, starting at a very early age.

All you need is one person, just one person who trusts and believes in you, and then you feel you can do anything. Unfortunately, a lot of children — like Michael, a former student of mine — don’t have even one person. Michael was an editor-in-chief of the Campanile, Palo Alto High School’s newspaper, in 2013, and his struggles represent those of many other young people.

For Michael, the pressures started early. “I had very strict parents,” he says. “They would tell me if I didn’t do well in school, I’d be homeless.” His early teachers weren’t very supportive either, and people misinterpreting his behavior and motivations became a common theme in his life. “I would get admonished,” he says, “by peers and educators telling me if I followed the rules and paid attention, of course I’d do better. It was almost part of my core being, to be this thing that was trodden on; everything I did turned into some kind of moral shortcoming.”

By the time he made it to my class, Michael described himself as “completely burned out like a pile of ash.” The school newspaper was the only thing he derived any meaning from, and still he could barely muster the will to show up. But he did. I got to know him as a bright but disconnected kid. He’d come into class and have no idea what he wanted to do or write about.

“To hear outside confirmation that someone believed in me… helped me not to crumble.”

I’ve seen so many students like this — they’re afraid but they’re also rebellious. They’re not cooperative. They’re difficult, even aggressive, and it’s because every single one of them feels bad about themselves. They’re constantly trying to prove to themselves — and to others — that they’re better than everyone thinks, but they’re constantly scared they’ll fall short.

During one of our production nights, Michael was struggling with music theory homework. “I was exhausted, trying to figure out this assignment,” he says, “and I was half-assing it.” Other students teased him for struggling, and he thought to himself, as he often did, “That’s right, I can’t do it.” I saw what was happening, walked up to the kids, and said, “He’s taking longer because he’s smart.” I knew deep down that Michael wanted to get it right, not just rush through it.

This was the first time that Michael had heard an adult say his abilities and intelligence were seen and respected. “To hear outside confirmation that someone believed in me,” he says, “even in the presence of other students who didn’t — it was awesome. It helped me not to crumble.”

That day was a turning point for him. He started to trust himself and called on this newfound confidence during his undergraduate years whenever he encountered obstacles or someone told him he’d never make it. He went on to earn a degree in neuroscience at Johns Hopkins, where he’s now a neuropsychiatric researcher. He’d found his one person to believe in him by accident, and it made all the difference.

Parents and teachers can sometimes forget how important we are in the lives of our children. We have so much control we have in shaping their confidence and self-image. And it all starts with trust, with believing a child is capable, even through setbacks, surprises and all the complications that come with growing up.

Trust empowers kids, whether it’s in the classroom or in the world at large, and the process of developing trust starts earlier than you think. Infants who are securely attached to their parents — who feel they can trust and depend on them — avoid many behavioral, social, and psychological problems that can arise later. A child’s fundamental sense of security in the world is based on their caregiver being someone they can rely upon.

Remember, trust is mutual. The degree to which your children can trust you will become reflected in their own ability to trust. Studies show that children rated as less trustworthy by their teachers exhibit higher levels of aggression and lower levels of “prosocial behavior” such as collaborating and sharing. Distrust in children has also been associated with their social withdrawal and loneliness.

“Many parents are operating from their own insecurities or doubts: Doesn’t their child need them?”

If we don’t feel trusted when we’re kids — or if there isn’t anyone close to us we can trust — we have difficulty getting over it. We grow up thinking we’re not trustworthy, and we accept it as a character trait. Like Michael, we become what we think we are, and we can suffer for it.

So how do we go about building trust in our children? We typically think of trust as handing our teenager the car keys and permitting them to drive on their own, or letting our 12-year-old stay home alone for the first time. But trust needs to start soon after kids are born.

Babies observe our every move as they learn how to get what they need from us. They know how to make us smile. They know how to make us cry. They may be dependent on us for everything, but they’re a lot more intelligent than we give them credit for. You need to respond to their needs, especially early on so they can feel you and their environment are trustworthy, but it’s also a fantastic time to start teaching your child some important lessons.

Many parents are operating from their own insecurities or doubts: Doesn’t their child need them? And if they don’t, what kind of parents are they? I firmly believe that you want your child to want to be with you, not to need to be with you.

This tension first arises with sleep. Your children can and will sleep on their own if you believe they can do it and if you teach them how. Kids learn to self-soothe, when given the opportunity, by sucking their thumbs, using pacifiers, or playing with toys. My daughters always had stuffed animals, and sometimes I’d wake up and find Susan talking to her teddy bear. Janet used to sing in bed. Because we’d built a relationship of trust, they learned they could entertain themselves and meet a lot of their own needs which meant that my husband and I got to sleep. A win-win.

As kids grow, they can be given more and more opportunities to build their own trustworthiness. The choices you make with your child will dictate the culture of your family. You always want to ask yourself whether you’re actively building trust in them or whether you’re shutting your child down. For young children, little achievements can build their trust and belief in themselves. They tie their own shoes, and it works! They put on their own clothes, and it works! They walk to school, and that works too! Through these small victories, they can see the tangible results of their efforts.

While you can’t always trust a small child to make intelligent choices, you can guide them in considering options and picking the best one. If I gave my nine-year-old grandson a lollipop and told him not to eat it, I know he still would. But if I explained why he shouldn’t eat it, that sugar isn’t healthy and might even give him cavities and that eating it before dinner will spoil his appetite, he could start to learn how to make better choices. OK, he might go ahead and eat the lollipop anyway, but as we work on these kinds of decisions over time, he would build the skills for living a healthy life and take care of himself.

“When we are fearful and hover over our children, they become afraid.”

Each age brings its own instances of trust. When my daughters were around 5, I’d ask them whether they were hungry and then I’d believe their answer. I did bring snacks with me in case they misjudged their hunger. If we were on a long car ride and they didn’t want to eat when we stopped for a meal, I’d explain we wouldn’t stop at another restaurant for several hours and I’d let them determine what to do. I trusted them with their eating decisions.

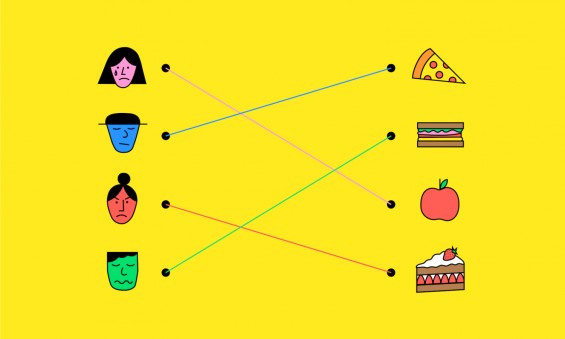

With teenagers, parents can cultivate trust in a series of steps. For instance, here is how I’d build trust with shopping, one of my favorite educational activities:

Step 1: The parent does everything, selecting and buying all items needed by a child.

Step 2: You trust your child to go with you to the store, and you allow them to make most of the purchasing decisions (giving kids a specific budget is a wonderful way to teach financial responsibility).

Step 3: You let your child gather the needed items on their own; the two of you meet at the registers at a set time and make the final purchases together.

Step 4: Once you’ve built a foundation of trust and taught your child how to be responsible with money, you can give them your credit card and let them shop on their own (many major credit cards allow you to add a minor as an authorized user). Of course, you’ll check the charges and teach them to verify the credit card statement with you at the end of the month.

Another way to gauge your teenager’s trustworthiness is by testing whether they make good on their word. They said they’d be home by 8 PM — were they? If they were late, did they call or text to tell you in advance? After they prove themselves trustworthy, increase their freedoms and responsibilities.

And if they still need to learn to come home on time, have a conversation about what went wrong and troubleshoot together for the next time. Some kids just have a hard time being on time, but don’t give up — give them more opportunities to learn. After all, time management is a skill that many adults lack, too.

If children aren’t empowered with trust and if they don’t feel trustworthy, they’ll have a very difficult time becoming independent. They won’t learn to trust and respect themselves. When we are fearful and hover over our children, they become afraid.

Excerpted from the new book How to Raise Successful People: Simple Lessons for Radical Results by Esther Wojcicki. Copyright © 2019 Esther Wojcicki. Used with permission from Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.

Watch her TEDxBerkeley talk now:

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Esther Wojcicki is an educator, journalist and mother of Anne (cofounder and CEO of 23andme), Susan (YouTube CEO), and Janet (Fulbright-winning anthropologist, pediatrics professor and researcher). A leader in blended learning and the integration of technology into education, she is the founder of the Media Arts programs at Palo Alto High School. Wojcicki serves as vice chair of Creative Commons and was instrumental in the launch of the Google Teachers Academy. She blogs regularly for Huffington Post and is coauthor of the book Moonshots in Education.

This piece was adapted for TED-Ed from this Ideas article.