How to grow your own tiny forest

When you look at a row of empty parking spots, what do you see?

Many of us would see it for what it is — a place that could be filled with cars and trucks.

But to eco-engineer Shubhendu Sharma, it’s a space to be planted with trees and turned into a compact yet mighty forest.

What’s more, he believes these tiny forests can thrive anywhere, including our most crowded and polluted cities where they can help maintain clean air and water and provide habitat for animals and insects. “A forest is not an isolated piece of land where animals live together,” says Sharma, a TED Fellow. “A forest can be an integral part of our urban existence.”

Most of us know just how essential trees are to our health and to the planet’s. Yet millions of hectares of forest are cleared every year due to farming, ranching, logging and construction, making deforestation one of the biggest contributors to greenhouse gas emissions. The World Wildlife Foundation estimates that 20 percent of the Amazon rainforest and surrounding ecosystems have already been lost, threatening a vital carbon sink, and Brazilian president Jair Bolsinaro is opening up previously protected parts to commercial development.

Inspired by the work of Japanese scientist Akira Miyawaki, Sharma built a forest in the backyard of his family’s home in northern India in 2010. An industrial engineer at the time, he planted 224 spindly young trees and shrubs In the 75-square-meter (or 807-square-foot) plot. They grew and flourished, and a dozen species of birds came to check them out. The plantings created welcome shade, and their roots were able to absorb even the abundant monsoon rains. After a year, he had his own forest.

Since then, Sharma has founded a company called Afforestt. Its top priority is to bring back natural forests to places where they no longer exist. This means restoring stable ecosystems of plants and animals that used to exist in these spaces. Such systems ordinarily take hundreds of years to evolve, grow and mature together, but Sharma believes it’s possible to do this in as little as 10 years — and he has plenty of examples to prove it. He’s shown you can take a space the size of six or seven parking spots — and create a lush, verdant forest with over 100 trees and shrubs. So far, Afforestt has planted 144 forests in 45 cities around the world.

So, how do you build a complete forest ASAP? By aiming for two things: Density and planting native species.

In terms of achieving density, it’s all about filling a space with trees and shrubs of varying heights. “By making a multi-layered forest, we can fill up an entire vertical space with greenery,” Sharma says. “That way, we can have 30 times more green surface area compared to a lawn or a garden in the same area.” A tiny forest provides a long-term, cost-effective alternative to a traditional lawn. Not only are trees beautiful and great at taking in carbon dioxide, they act as an effective noise buffer and a sponge for air pollution and particulate matter.

Planting trees that are native to your region has specific benefits. Since they’re already adapted to the climate, they require significantly less maintenance than many other non-native species. Native trees also create a welcoming environment for the indigenous wildlife — birds and insects — to thrive. Early studies indicate that these dense forests may actually be able to restore biodiversity at levels comparable to natural forests.

Ready to create your own tiny forest?

Shubhendu Sharma breaks it down into 5 steps:

1. Identify your native species

When beginning a project, Sharma and his team first go to the nearest national park, protected grove, or nature reserve to search for patches of conserved forest. Paying close attention to the number and types of trees in a natural ecosystem will allow you to build your own, he says — for instance, noting the relative proportion of native species will give you an idea of how many to plant. “If you can, collect the seeds, germinate seedlings out of them; that’s the start of the physical work,” he says. (Editor’s note: This is not legal in some places, so please check first.)

If you can’t collect seeds or aren’t legally permitted to do so, you can also ask someone knowledgeable at a local nursery, garden, or agricultural or county extension agent to recommend native species to plant.

2. Nurture the soil

Healthy soil is the basis of a healthy forest. “Find different types of biomass, or organic matter, that can make your soil moist, full of nutrition, and so soft that roots can penetrate into it easily,” Sharma says. His team often uses coco-peat (also known as coco coir; it’s the fibrous husks from the outer layer of a coconut) because it’s highly absorbent and improves water retention in dry soil.

“To loosen up compacted soil, we use pear tree husk or any biomass, which is crunchy in nature,” Sharma elaborates. Peanut shells are OK too. He adds, “It has to have a spring-like property. When you crush it, it should come back to its original shape.” These characteristics are important to help support the roots of your trees.

Instead of adding nutrients or artificial fertilizers, Afforestt adds microorganisms. “We take soil from a natural forest, so we can get the native colonies of microbes and fungi and we multiply their number in what we call compost tea,” Sharma says. Compost tea is a microbe-rich nutrient broth, which is diluted and added to the soil. These fungi and microbes grow and support the root network to allow trees to grow quickly and collectively. While more studies are needed to better understand compost tea, you can add regular compost, which is known to support soil health.

3. Plant your seedlings — but don’t forget the mulch

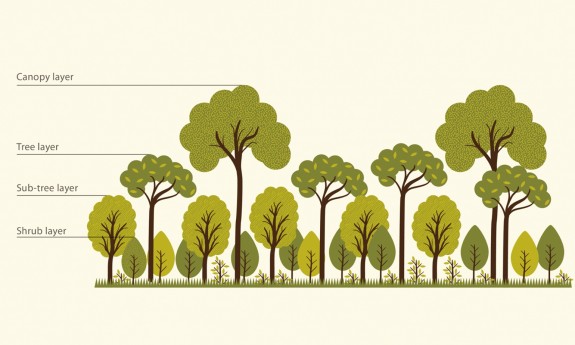

The key to achieving a dense forest is to arrange the landscape in a beneficial ratio of layers. “We divide our trees into four different layers: a shrub layer, sub-tree layer, a tree layer, and a canopy layer,” Sharma explains. The exact ratio of these layers depends on where you live. For example, a rainforest environment like São Paulo will have a denser canopy layer, while a region with a desert-like climate will have more shrubs. The most successful forests will mimic the composition of the natural environments found in your area.

What really sets the stage for rapid growth is the density of your layers. As trees grow, they communicate through fungal networks that protect against disease and provide nutrients to one another. Mulch plays a vital role in protecting the ecosystem below the soil against harsh environmental conditions — like a breathable, protective blanket over the soil for all seasons. Sharma’s team usually uses straw, but he says the right mulch can be “anything that doesn’t allow water to evaporate back into the atmosphere but is open enough to let the water seep through and reach the soil.” Not only does mulch protect the soil microbiome, it also traps moisture when it’s hot and protects against frost and ice when it’s cold.

4. Tend for a few years

Once your seedlings are planted, you’ll need to perform routine maintenance — watering and weeding — during the first couple of years. But there’s one thing the Afforestt team never does in this time period: They never prune or trim the trees themselves. Since the ultimate goal is to create a lush forest, pruning will counteract that growth process.

Plus, after you reach a certain stage of growth, you’ll be able to stop weeding. “Eventually, the forest becomes so dense that sunlight won’t reach the ground any more. Once sunlight cannot reach the ground anymore, weeds also can’t grow because they need sunlight,” Sharma explains.

5. Let it grow!

Humus is the organic material that naturally occurs in healthy environments. Once it begins to form, then you’ll know it’s time to let your forest be. “Humus is the food for the forest,” Sharma says. “It can only be made on the floor of a natural forest, because it’s a combination of biomass, fungi, dead bodies of insects, microorganisms, earthworms, etc.”

How do you know when humus has formed? “Initially, you will see just leaves on the forest floor, then twigs, and then you’ll see old branches fall, termites coming in to convert that branch into powder. It gets more and more complex and rich,” Sharma explains. “This is the stage when we say, ‘Ok, now no management is the best management.’” Forests can typically be left alone after three years.

If you don’t have the space or time to build your own forest, you can participate in other ways. “What I’d really urge people to do is to go to their local natural forest and learn about their native trees,” says Sharma. Most of us can name multiple dog or cat breeds or the names of numerous fruits and vegetables, so add to your knowledge by learning the names of 25 native tree species. Then look for them in your community.

To expand the Afforestt network, Sharma is partnering with collaborators in other countries and developed a crowdfunding app called Sugi. This allows people to donate and fund forest projects, building a global network around rewilding urban environments. Sharma hopes that by planting seeds of inspiration, the reforestation movement will spread so that more and more land is converted back into forests. While the Afforestt team started in India, it has consulted with groups from many countries, including Cameroon, Australia and Japan. They’ve developed an open-source database with best practices that anyone to use and maintain an up-to-date guide on reforestation.

By planting tiny forests all around the world, Sharma and his team hope to open up people’s eyes to the variety and splendor of native plants. “The biggest challenge is that our perception of beauty has to change,” he says. “There is no one-size-fits-all formula, because Earth is extremely biodiverse. If you go to Dubai and Spain, you see palm trees and if you go to California, you see the same palm trees. That’s a boring world, you know? The beauty of a natural forest is that it’s different everywhere and there is so much to learn. There is so much to enjoy.”

All images: Courtesy of Afforestt.

Watch his TED Talk now:

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Kara Newman is a science journalist currently based in New York City.

This piece was adapted for TED-Ed from this Ideas article.